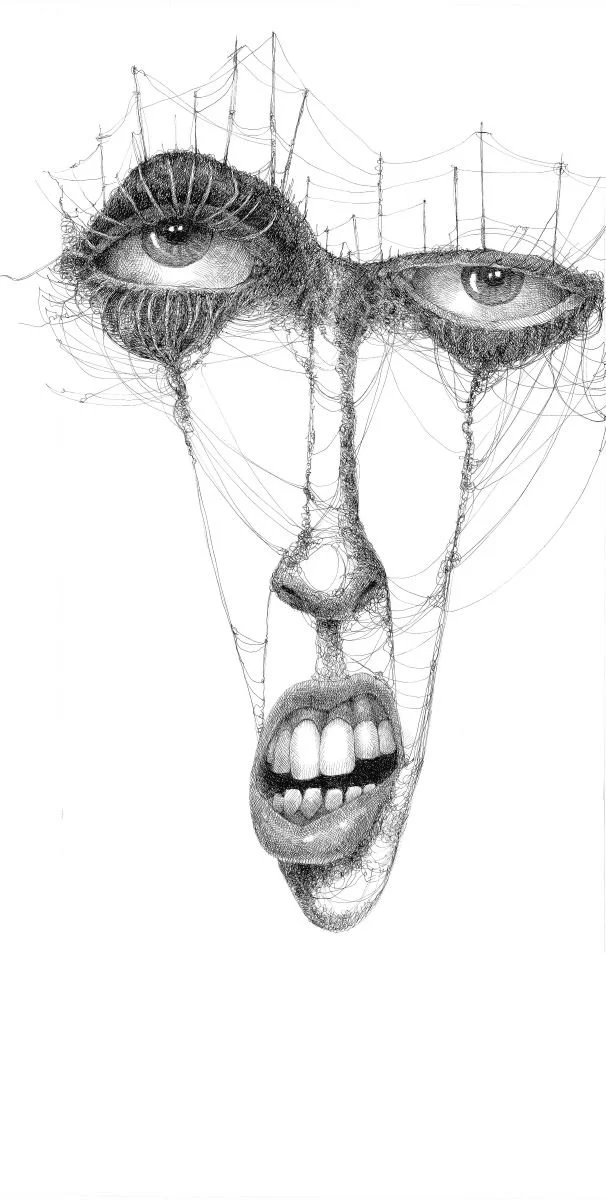

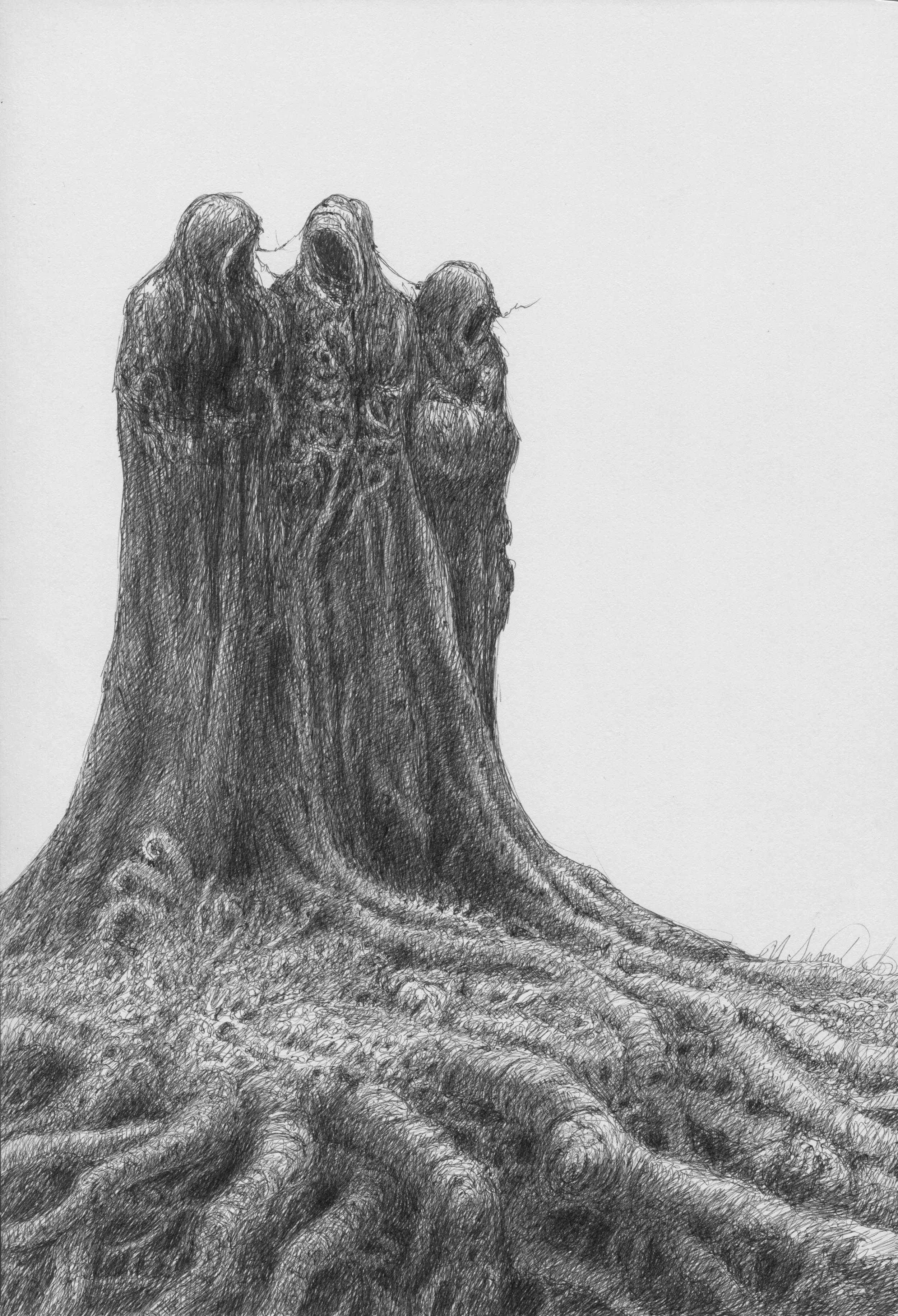

I have two drawings I did after the 2024 election: The Information Age and Tribal.

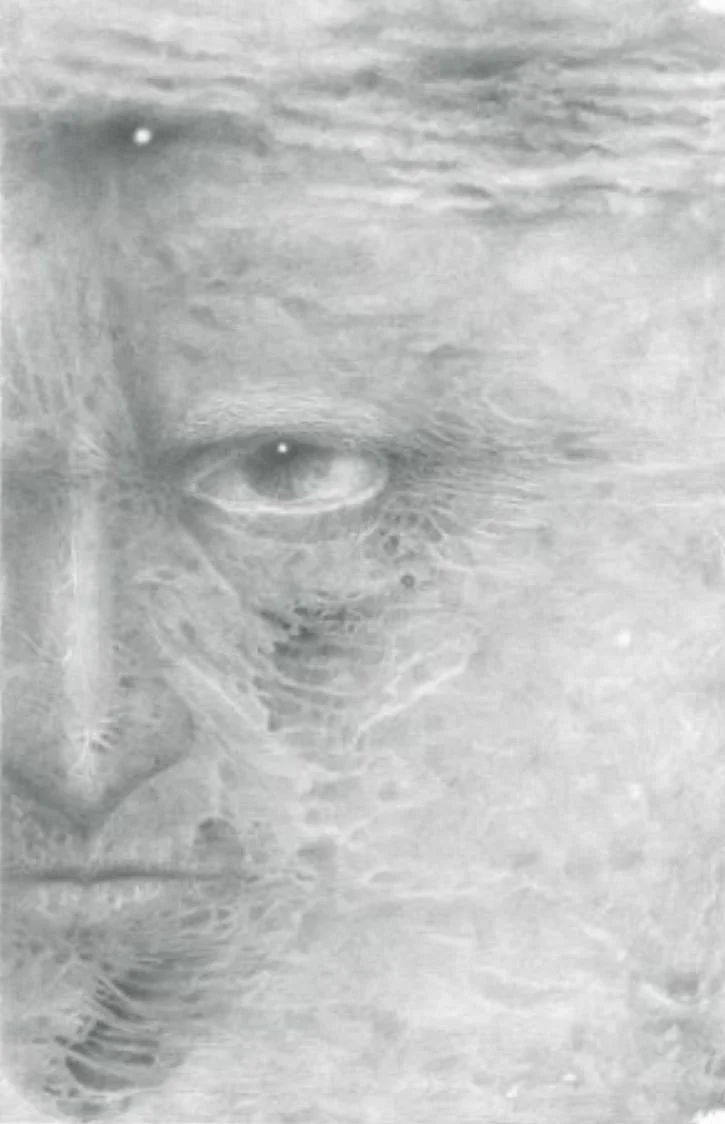

Human civilization has been divided into eras: the hunter-gatherer age, the agricultural age, the industrial age, and the information age. Each era is defined by its dominant characteristic. We currently live in the Information Age. With the exponential use of social media, this age is producing unanticipated difficulties, one of which is our ability as a society to have a common understanding of what is accurate or true. When a society cannot agree on what is happening, we become conflicted about existential dangers to our local community, country, and planet.

The fundamental problem with our current informational lives is that we all live in different informational tribes. Each tribe focuses on various social and environmental issues and gets information from different sources. As human beings, we all have biases. These biases guide us in what information is valuable to our beliefs. The information we gather reinforces and builds our beliefs to absolute certainty. One tribe's certainty is another tribe's ignorance. With all of us bewildered by each other’s tribe, we become angry with each other. This anger is used by those with wealth and power to control all of us. There is no religious group, no civic group that is not manipulated into doing what someone else wants us to do.

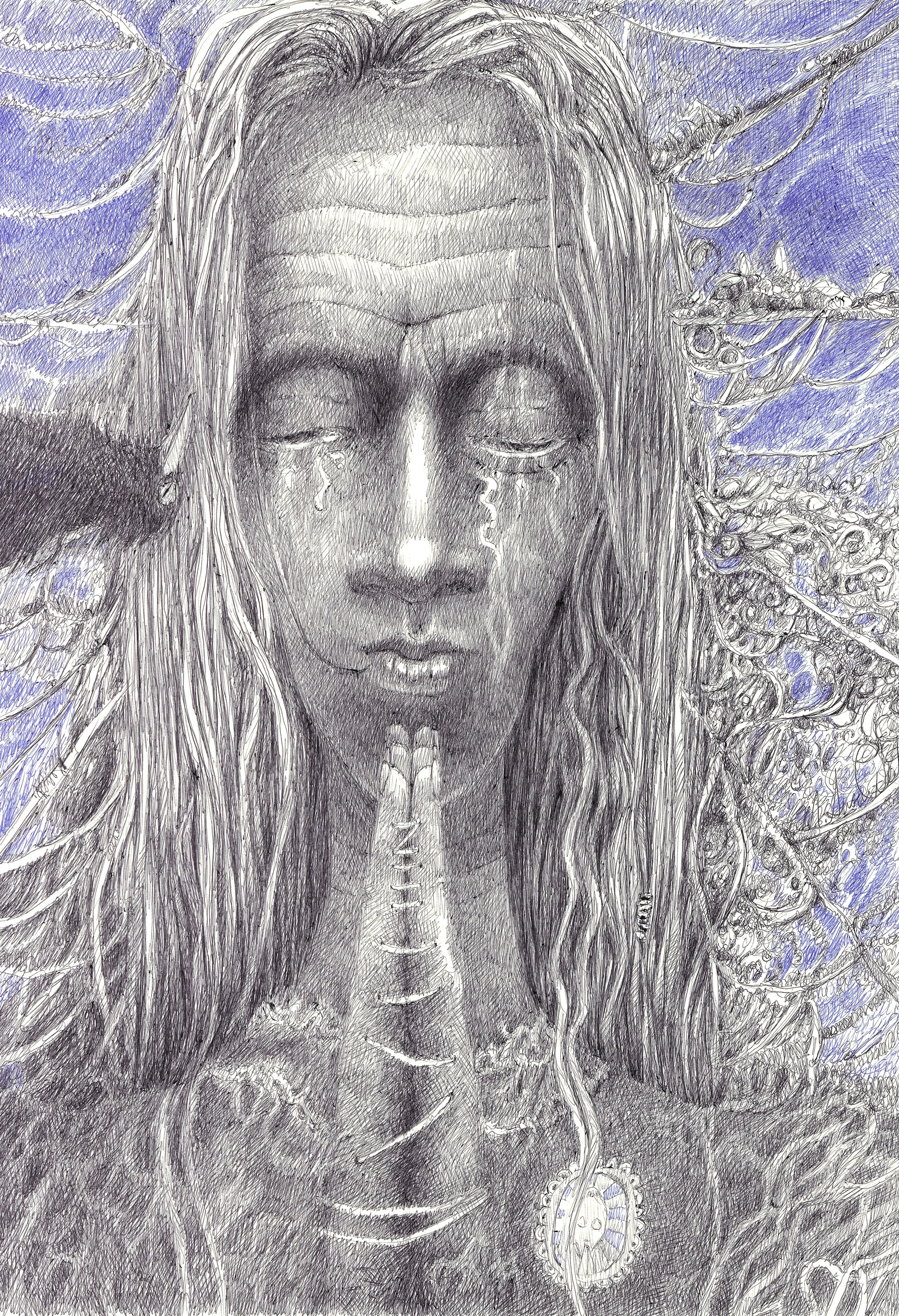

There are, however, elements of truth that we can look at amid the noise and anger. The measurement of any truth is its connection to nature. The health of our natural world connects all of us. We must all strive for clean drinking water, clean air, and natural food for ourselves and our grandchildren. For our politics to mean anything, it must include these essential things.

Nature needs to ground our truths because nature is our lifeline. We must all learn to appreciate the trees that produce our oxygen, the distant mountains that explain our spiritual connection to beauty, and the power of water to transform the landscape and how life follows its transformation. To see the truth, walk in the woods, by a river, in the high desert, or alongside the ocean waves. Learn to appreciate this incredible life and see it with the eyes of wonder, curiosity, and care. Let these true things guide the information you seek and the politics that protect them. Look to the stars to find your place in the universe and know you are made of stardust where anything is possible.

The Information Age

Tribal